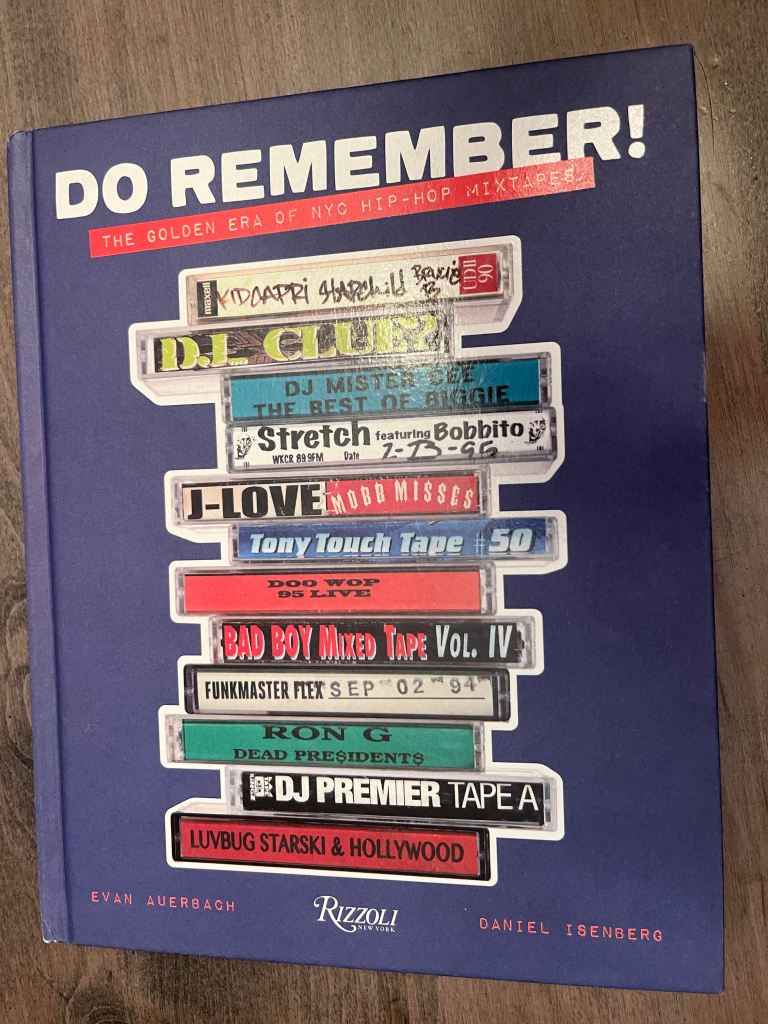

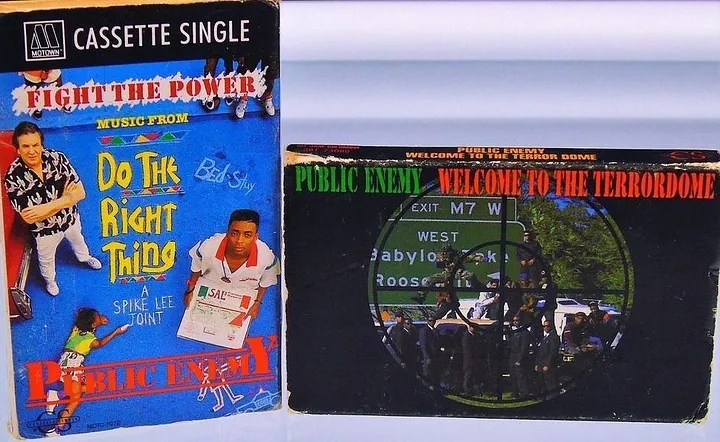

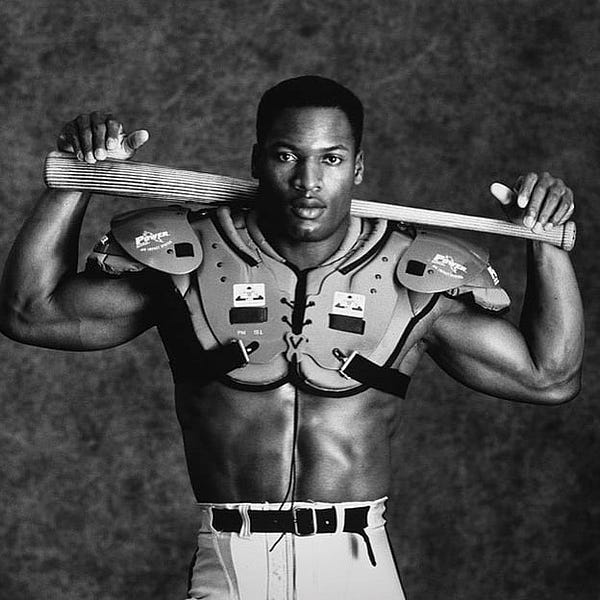

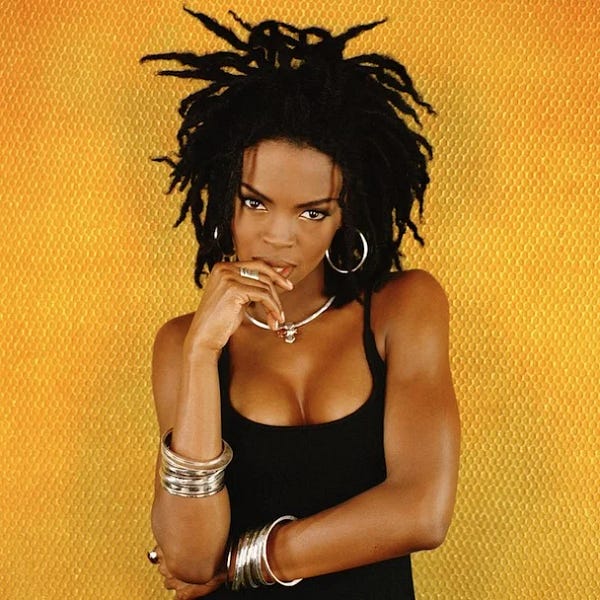

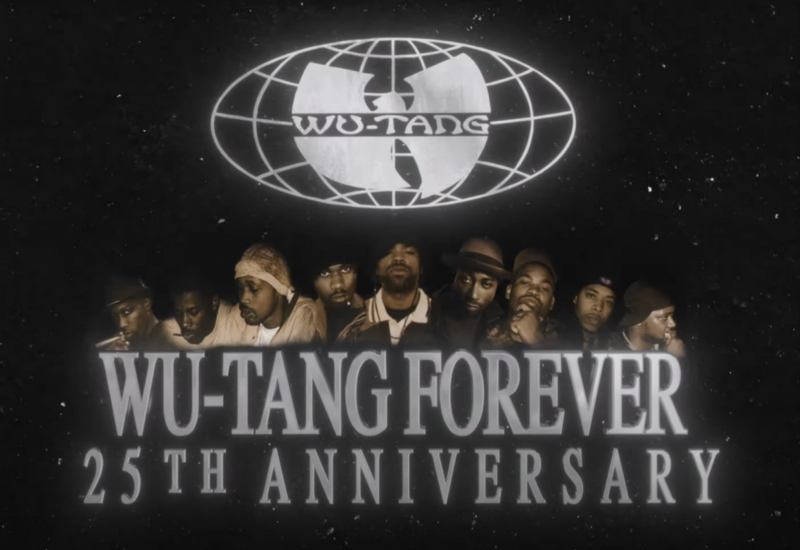

While it is not considered one of the four original elements, fashion has been an indelible part of hip-hop from the beginning.

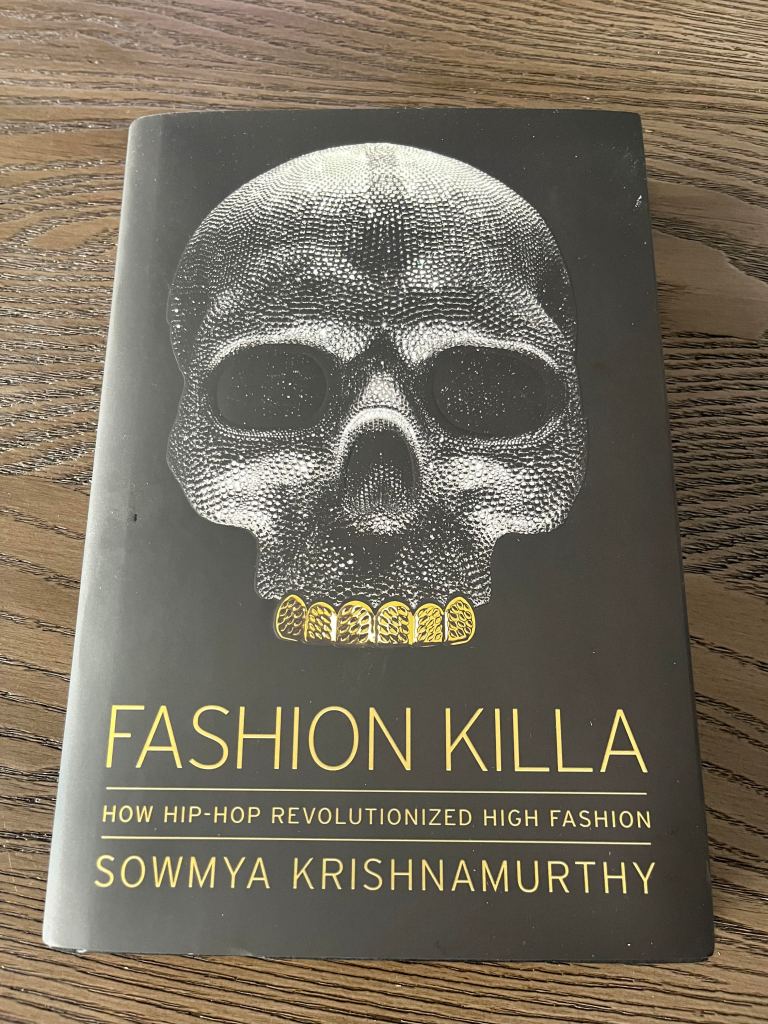

How an artist looked was oftentimes just as important as how an artist sounded, something that has only intensified as hip-hop and high fashion have become intertwined.