“If the way to do good to my country were to render myself popular, I could easily do it. But extravagant popularity is not the road to public advantage.”

— John Adams

John Adams is the most underrated Founding Father.

He was also the realest.

While George Washington was so great as to be deified and Thomas Jefferson was an enormous, hypocritical dickhead, Adams was blunt, honest, and flawed. He once said, “No man is entirely free from weakness and imperfection in this life,” something you can’t imagine many other Founders expressing.

John Adams has been my favorite historical figure since I first truly learned about him in college. One professor described him as a “curmudgeon” and while he meant it as a criticism (he worshipped at the altar of Washington), I immediately identified with it.

I was a fan immediately, but over the past two decades, as I’ve continued to study him thoroughly, I now call him my hero. I don’t use that term lightly, the way some do for athletes and entertainers, but it fits in this case because John Adams was a major force in securing American independence and, subsequently, shaping the modern world.

Living near and then within Philadelphia, the birthplace of American Independence, for the first thirty-four years of my life, I was often enveloped by the history of the Revolution. Yet while Adams certainly made his mark in Philly — first as part of both the First and Second Continental Congress, when he served as the “Colossus of the floor,” in Jefferson’s words, and later when he occupied the President’s House at 5th and Market, merely a block from where he had fought so hard for independence twenty years earlier, for almost the entirety of his presidential term — he’s practically forgotten in the city. The vast majority of statues, streets, and bridges are dedicated to Benjamin Franklin, while most of what remains goes to George Washington.

Adams had predicted as much. In a letter to friend Benjamin Rush, he wrote that history would remember the legacy of 1776 as, “Benjamin Franklin smote the ground, and out sprang George Washington, fully grown and on his horse. Franklin then electrified them with his miraculous lightning rod and the three of them — Franklin, Washington, and the horse — conducted the entire Revolution all by themselves.”

Adams, once again, was overshadowed by the two.

Monuments will never be erected to me . . . romances will never be written, nor flattering orations spoken, to transmit me to posterity in brilliant colors.”

— John Adams

There was always a void. I wanted to see a statue of Adams, but there were none to be found.

For four years, my office was at the corner of 6th and Chestnut streets in Philadelphia, across the street from the Liberty Bell, diagonal from Independence Hall, only a block from the President’s House, and two blocks from the home where Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence. I was in the heart of the nation’s conception, but it also felt lacking because there was almost nothing commemorating Adams.

It’s not just in Philly. It’s everywhere. Even after being the subject of a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography and an HBO adaptation that won more Emmy awards than any other miniseries ever, there is no national monument to the nation’s first Vice President and second President.

Congress approved an Adams Memorial to be built in November, 2001. Set to feature not only John, but also Abigail, their son and sixth President of the United States, John Quincy, and several other members of the family, the project has languished — its deadline has been extended twice but no construction has begun. In fact, only two of the twelve members of the Adams Memorial Commission have been appointed thus far.

John Adams remains the overshadowed Founder.

Fortunately, there is one place that recognizes the impact he had on the world: his hometown of Quincy. Originally part of Braintree before splitting off to become a separate town, Quincy is located ten miles south of Boston and is where Adams lived his entire life…if you don’t count all the years he spent in England, France, the Netherlands, and Philly, of course.

Although I had been to Boston, I had never visited Quincy. It was always a hope, but life seemed to always conspire to prevent me from making the trip. Fortunately, our summer vacation plans had us driving through Massachusetts, so I suggested that we stop to visit Mr. Adams and my wife — always so supportive of my pursuits and interests — was all for it. We would begin our trip a day early and spend a night near Quincy before heading to Maine.

We hit more traffic than expected and had to make more pitstops than planned, but after more than twenty years, I finally made it to the birthplace of my hero.

As I discovered while researching the trip, it’s actually a blessing I waited so long. Within the past few years, a dedicated Hancock Adams Common has been built, with new large sculptures of both John Hancock and John Adams (and a previously unplanned new one of Abigail after a groundswell of support), and additional statues of John and Abigail with a young John Quincy were placed in storage for a time before being moved to nearby Merrymount Park.

He said monuments would never be erected to him, but in Quincy there is much more to commemorate the Adamses than ever before.

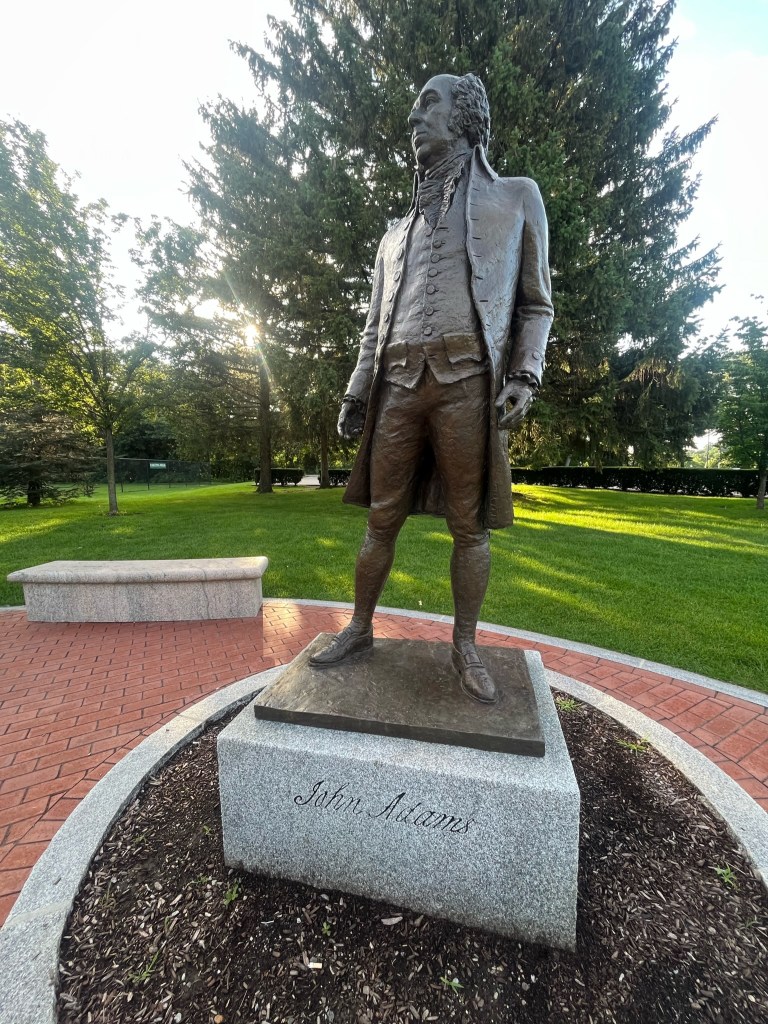

Upon arrival, we were able to visit Hancock Adams Common before heading to the birthplace houses and then to the Old House. I was overcome as I approached a statue of John Adams for the first time in my life. I stopped to take it in and thought about how underappreciated he has been for two centuries. My wife said that I had the same look on my face as I do when I visit my best friend’s grave. I’m not sure what that means, but I hope it’s a good thing.

Seeing the homes where John and John Quincy were born was very cool, the tour guide was good and knowledgeable, and, as with all sites like this, it was both fascinating and jarring to not only be in the same location as a historical event, but also to see how people lived back then.

Yet when I looked around outside, it was a bit hard to envision what it was like back then. Today, like most of the other Quincy historical sites, it is surrounded by modern America. The homes are now at the corner of a skewed intersection of two fairly busy streets, with a liquor store, an Edward Jones financial advisor, a Dunkin’ and a 7-Eleven within a block or two. Quite different from 1735. Also, the street is named Franklin, which I don’t think John would have appreciated.

From there, we went to the Old House at Peacefield.

Located about a mile-and-a-half from the birth sites, this was the home the Adamses purchased before returning from England. Upon seeing the home, Abigail said it felt like a “wren’s nest,” smaller not only than she had expected, but also in comparison to the splendor in which they had lived abroad.

When we saw it, I was perplexed by Abigail’s comment because the house is quite large, with a stunning detached stone library and an elegant garden. It was only when I was reminded that the home had been renovated and expanded twice by succeeding generations that her complaint made sense.

Unlike the birth houses, we were actually able to go upstairs and saw the room where John spent much of his final years, in his armchair surrounded by his books, and the bedroom where Abigail died.

The tour guide was great, the perfect mix of historical knowledge and public performance that can elevate these types of things. Due to the fact that even the improvements and additions are over a century old, it wasn’t always easy to imagine what the home was like when the Adamses lived there, but there was enough character and history — including the original front door, some of Abigail’s actual home tools and John’s presidential china — to provide an adequate picture.

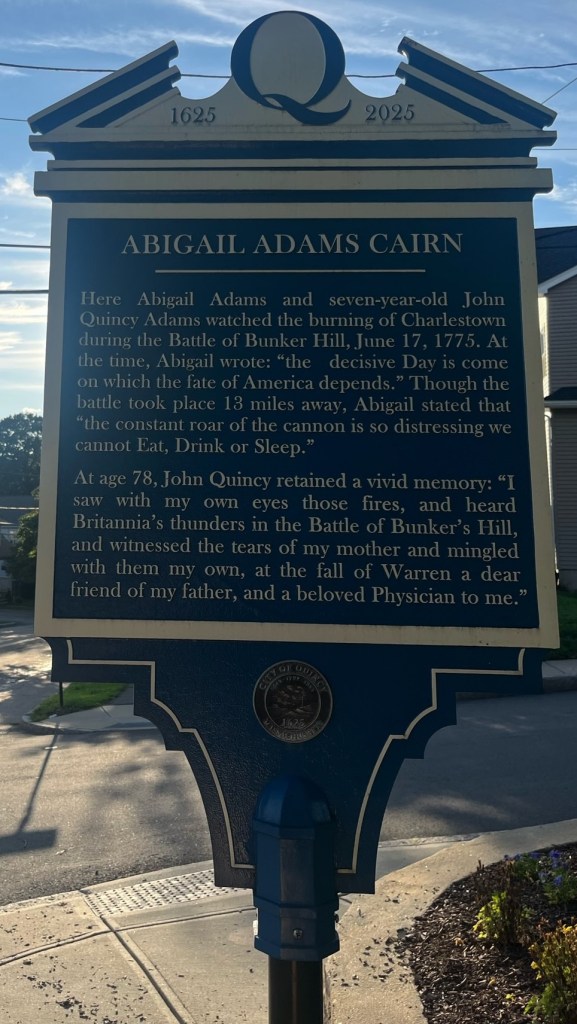

Everyone was famished by that point, so we found a nice little Italian restaurant for dinner. When we finished, as we were planning on heading to the hotel, I realized we may be close to another important locale. I did a quick search and in only a few minutes we were parked in front of the Abigail Adams Cairn.

Located atop Penn’s Hill (a landmark that is prevalent in Adams’s writings), it is the spot where Abigail took John Quincy and daughter Nabby to watch the burning of Charlestown thirteen miles away. Even today, standing next to the cairn, you can see the buildings of downtown Boston in the distance. Like much of Quincy, contemporary life has sprouted all around the historical site, as the cairn is surrounded by modest, tightly-packed, modern homes.

The kids were exhausted after our long day of travel and tours, so we made our way to the hotel in Braintree, where we relaxed for the rest of the night. I was tired and not overly enthusiastic about another four hours of driving ahead of us, but I was happy with the day if slightly disappointed as there were a few items on my list that we weren’t able to get to.

The next morning, I was the first one awake. Rather than waste the purity of a beautiful Sunday morning by staying in bed and mindlessly scrolling on my phone, I popped up, got dressed quickly and quietly, hopped in the car, and headed back to Quincy.

I drove to the corner of Burgin Parkway & Dimmock Street, where there is a John Adams statue in Freedom Park, a narrow, block-long park without any parking that runs between a busy street and a set of railroad tracks. I only knew about it because we had happened to drive past it the day before.

After visiting with that iteration of Adams, I walked a few more blocks and saw a large statue of John Hancock commemorating the site of his birth. I then made my way to the outskirts of town to Merrymount Park, a piece of land that was a gift from Charles Francis Adams. A sprawling, 80-acre public area featuring an amphitheater and several sports fields, it also includes a small walking track that features two statues — one of Abigail with John Quincy, another of John — thirty feet apart.

Previously, they had been situated to face one another from opposite sides of Hancock Street, meant to symbolize the years Adams spent away from home in service of his nation. Now, you can take them both in without the interruption of cars or other aspects of regular life.

Personally, I prefer it this way.

After breakfast at the hotel and packing the car, we stopped by the Adams National Park Visitors Center for souvenirs, where the staff was great — the kids were given free colonial hats that they used to pretend they were pirates. As we departed Quincy and headed towards Boston, a trip John Adams made many times in his life, I was satisfied with our sojourn. I had seen everything I wanted to see.

Well, except for one.

“To be good, and to do good, is all we have to do.”

— John Adams

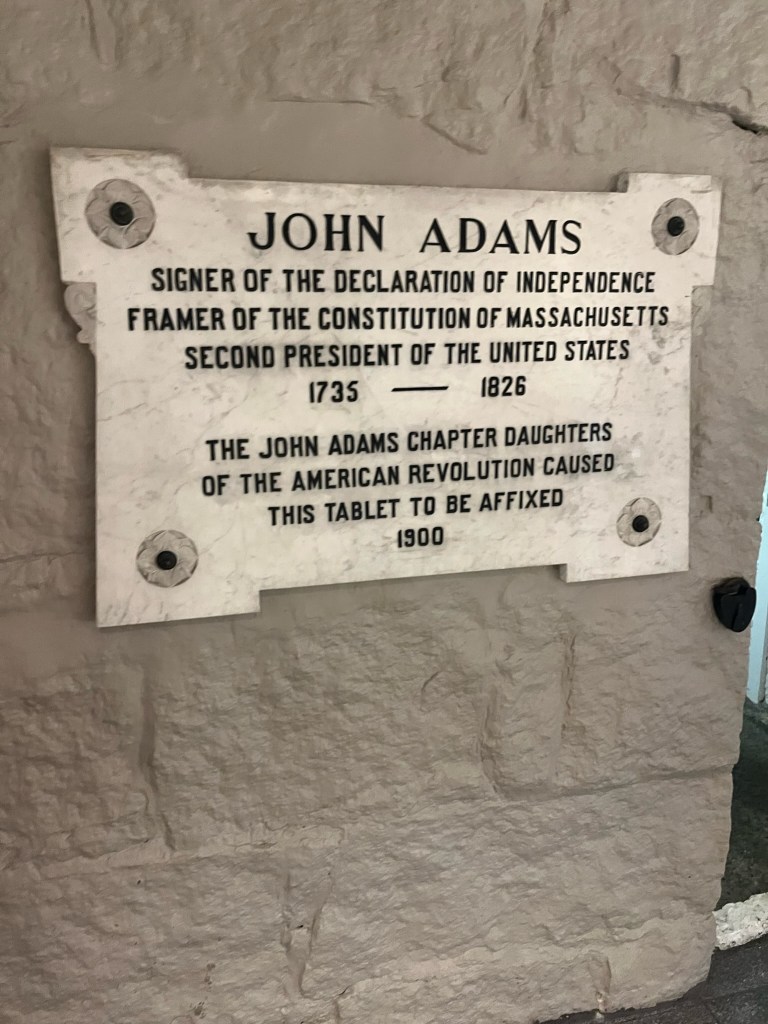

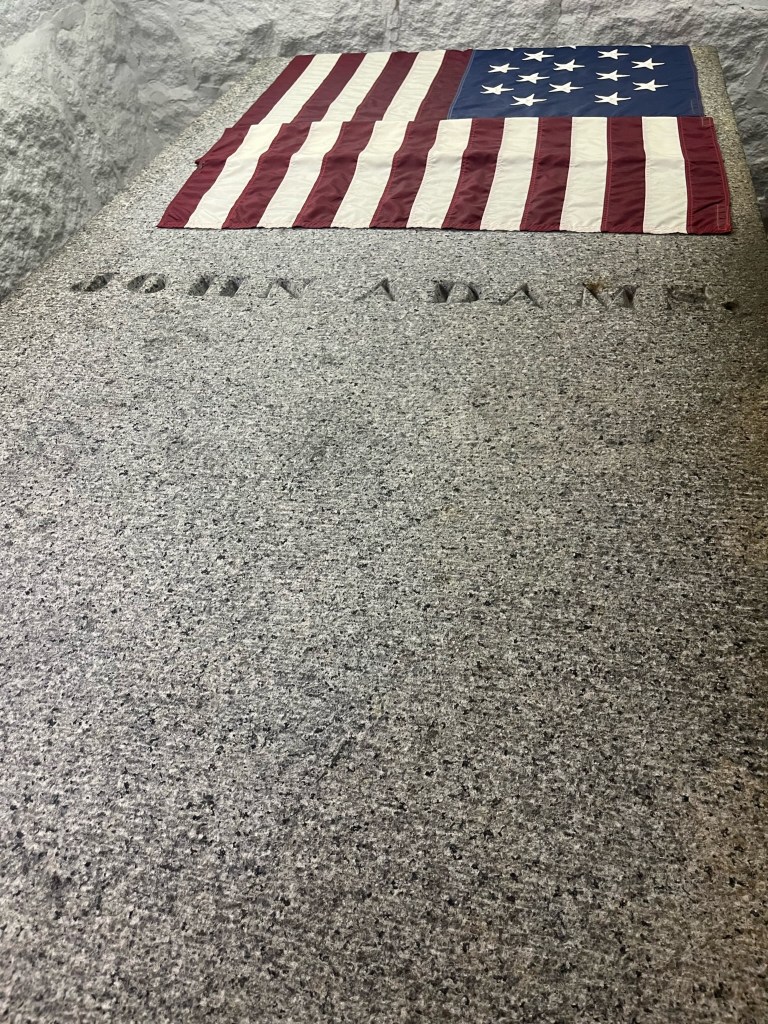

The combination of traffic and short operating hours prevented us from visiting one place on my list: the Church of the Presidents, where the crypts of John, Abigail, John Quincy, and Louisa Catherine Adams are located beneath the location of the church where the Adams family worshipped.

I was slightly disappointed, but it was towards the bottom of my must-see list. I saw the statues and the houses. I was all set.

My wife, however, kept insisting that we check it off the list on our way home, not only for me, but because it would help to break up the eight-hour drive and give us a chance to stretch our legs.

So we did…barely. Despite our best plans, we pulled into town with less than thirty minutes remaining before it closed for the day. We raced to the church and, after the people with thick Massachusetts accents made fun of the way we talk, were told that we were too late for the church tour but that he could take us to the crypts.

If only he knew. I never really cared about the church tour at all.

So we descended down the stairs and, after hearing some history about the church, made our way around the corner to the room that housed the four crypts. It was small and tight, but I did feel a sensation of something standing there.

I had seen the full picture, visiting where John Adams had been born as well as where he was ultimately laid to rest.

They say never meet your heroes, but that I disagree with that notion.

I couldn’t have a dialogue with him the way I did with Ryan Holiday or members of Wu-Tang, but a statue of Adams is as close as I could get, and I wasn’t always sure I would get the chance to see one.

Upon seeing this photo, a friend said, “You look genuinely happy.”

Do yourself a favor and meet your heroes.

Christopher Pierznik is the worst-selling author of nine books. A John Adams superfan, he has also written about a variety of other subjects for XXL, Cuepoint, Business Insider, The Cauldron, Fatherly, Hip Hop Golden Age, and many more. Find more of his writing at Medium and connect on Facebook. Please feel free to get in touch at CPierznik99@gmail.com.