A few weeks ago, Marshall Mathers III, known to the world as Eminem, released an eight-minute track titled “Campaign Speech,” in which he takes aim at all sorts of individuals, most especially Donald Trump.

While much of the reaction to the rhyme was based on its lyrical content, I was struck by something else entirely: there’s no beat. It isn’t completely a capella – there is supporting orchestration present throughout – but there’s nothing to bob your head to, no bassline.

While this is rare throughout much of hip-hop, this is not new territory for Eminem. Over the past year and change, he has spit rhymes sans a beat every chance he’s gotten, from his six minute polemic on “Sway in the Morning,” to the intro on last year’s D12 mixtape, Devil’s Night, to even the Shady CXVPHER, where he managed to convince (force?) Slaughterhouse to also eschew any musical backdrop.

This is how Em raps now. Since the beat is a nuisance, something that gets in the way of his unending tirades, he forgoes one every chance he gets. He knows that he can’t get away with that on albums, so he now chooses instrumentals that allow him to race all over the track without having to worry about staying on beat, a fact that was broached in Pitchfork‘s review of the awful Shady XV compilation:

“Even at his peak, his rapping was never melodious, but at his nadir, he has all the musicality of a leaf-blower. The production functions simply, like a stopwatch: It’s there to tell him when to start and when to stop, and occasionally a juiced-up power-rock chorus interrupts him. Submitting production to an Eminem album must feel, for a producer, something like a novelist feeding their manuscript into a wood chipper. On the one hand, you are guaranteed unprecedented exposure, and on the other, you are all but ensuring that no one will notice a note of your work.”

In the early days, Eminem was the ultimate MC, someone that could ride any beat at any time. While I’m convinced he can still do so, he consciously chooses not to.

So what happened?

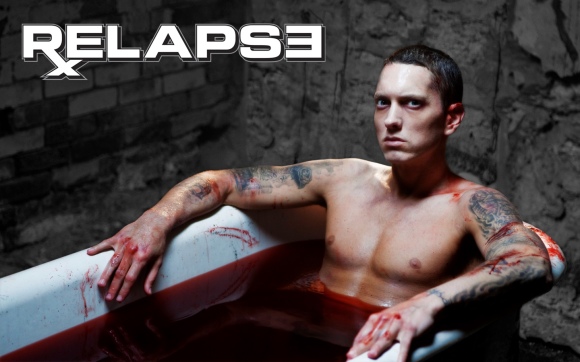

Relapse.

In 2009, anticipation for a new Eminem album was sky high.

It had been five years since he had released a solo LP, Encore, and in that time he had completely succumbed to drug addiction. His weight ballooned, presumably because of the effects the drugs had on his body:

“The coating on the Vicodin and the Valium I’d been taking for years leaves a hole in your stomach, so to avoid a stomachache, I was constantly eating — and eating badly.”

He was even rushed to the hospital due to an overdose – a Shady Records statement at the time called it “pneumonia” – and canceled his European tour so that he could check into rehab. Upon his release and completion of the twelve-step program, he returned to the studio. The new album, Relapse, was released on May 19, 2009 and it struck most as a letdown. I wrote an impassioned defense of Relapse in my last book, but I was one of the few – along with Tyler, the Creator and fans that found it to be a complex concept album – that appreciated it. Most found it to be a regression, disappointed in the horrorcore style and baffled by the accents Em employed at times.

When Relapse was received not as the work of a conquering hero returning to his kingdom, but as a disappointing grasp at previous relevance and shock value, it led to Eminem himself criticizing it – “Fuck my last CD, that shit’s in my trash” – and completely changing his approach.

Part of the initial excitement leading up to Relapse was that the entire album would be produced by Dr. Dre. In fact, Dre blocked off two months to work solely on the album and provided Em with dozens of beats. But after producing every song on Relapse save one – “Beautiful,” which Em produced himself and recorded before checking into rehab – Dr. Dre has produced a total of two Eminem tracks since, both for Recovery (one coming as an iTunes bonus track). While Dre had never previously supplied an entire album’s worth of songs to Em – he provided three tracks on The Slim Shady LP, six on The Marshall Mathers LP, three on The Eminem Show, and eight on Encore – his sound had always been included. No longer.

Originally, the plan had been that Em would release a second album from the same recording sessions, Relapse 2, something that he even made mention of on a skit towards the end of the original disc. Instead, after seeing the reception to Relapse, Em scrapped the sequel and instead released a seven track EP, Relapse: Refill, that included the previously released posse cut “Forever” with Drake, Kanye West, and Lil Wayne.

He then began recording completely new material with different producers that provided him with far different sounds. The result was Recovery. From the inspirational lead single, “Not Afraid,” to featuring Pink and Rihanna, songstresses he probably would have lampooned in previous years, it was repeatedly received as the work of an artist that was finally maturing. The album was more successful both critically and commercially – “Love the Way You Lie” was number one for seven consecutive weeks – and within those updated flips of power rock ballads, Em had found his new formula. Who needs Dr. Dre’s backbreaking production when you can go number one without it?

He employed it for his high profile collaborations with Lil’ Wayne (“No Love,” which sampled Haddaway’s “What Is Love”) and Kendrick Lamar (“Love Game” was based on Wayne Fontana & the Mindbenders’s “Game of Love”), as well as for the title track on his Shady XV compilation, which sampled Billy Squier’s “My Kinda Lover.” Ironically, even “Berzerk,” the stellar Beastie Boys-homage throwback to pure ’80s hip-hop, sampled another Squier song (“The Stroke”). Rick Rubin had perfected the rock/rap hybrid on Licensed to Ill and Em tapped him to update it for The Marshall Mathers LP 2.

Perhaps the clearest example of this shift can be seen on Eminem’s radio appearances. Compare the freestyles of the past eighteen months at the top of this post to a visit Em made to The Tim Westwood Show while promoting Relapse.

Along with Mr. Porter, he glided over several different beats, taking his time and following the rhythm rather than simply trying to cram as many words into a bar as possible. It was vintage Em:

There have been glimpses of that artist over the past half-decade – “Evil Twin” off The Marshall Mathers LP 2 is a perfect example – but, by and large, Em’s stock and trade has been a capella freestyles to promote albums with “chains of these rhyming lines…erected into dizzying towers” over soundscapes that were popular three decades ago. Can you imagine if 1997 Puff Daddy produced an album for 2016 Eminem?

I’m not one of those fans that expects or even wants an artist to continue doing the same thing over and over. I like growth, change, and progression, but I also like for my emcees to keep some sort of melody when they rhyme, something that Em does less and less as time goes on. Will this trend continue on his new album? I have no idea. He’s proven in the past that he can go into the lab and emerge with a completely different sound, like a singular rap version of U2.

As time goes on, however, it seems like the backlash to Relapse broke Eminem’s brain, specifically the part that kept him on beat.

Christopher Pierznik’s nine books are available in paperback and Kindle. His work has appeared on XXL, Cuepoint, Business Insider, The Cauldron, Medium, Fatherly, Hip Hop Golden Age, and many more. Subscribe to his monthly newsletter or follow him on Facebook or Twitter.

One reply on “The Reaction to “Relapse” Changed Eminem”

I felt the same way after hearing Campaign Speech albeit, if it’s 1 or 2 songs within an album that are like that, it’s a nice switch up and artistic freedom. However, a whole album without the fun melodics just isn’t as enjoyable for myself – it was what always set him apart! I’m from the old school of rap (90s) though &, maybe the newer gens are into that style?

LikeLike